Zoe Stevens

Zoe Stevens

In today’s world, farming is difficult and crop and livestock values are impacted by the strong pound, global commodity prices and insecurity about what shape agri-environment schemes will take once we’re no long part of the EU. Wildlife needs space to adapt and move in order to cope with climate change and farmers are increasingly faced with unpredictable weather patterns that impact on profitability, planning and resource use. Our vision of a Living Landscape is to build a network of large areas linked by corridors that can provide benefits for people and biodiversity and, as originally planned, at Lower Smite Farm we’re developing and exploring new ways of farming in order to maximise the benefits to wildlife whilst finding profit. To understand why it’s important that we do this, it’s crucial to look at the history and bigger picture of farming.

We’re lucky enough to have farm diaries for 1908 to 1919 that give us an in-depth account of how the land was managed during wartime when food security was dangerously low and wildlife was still a-plenty. In 1910, the new tenant of Lower Smite Farm purchased two 4yr old heavy horses and an ageing mare for £88 to do the bulk of the heavy work such as cultivation and planting. The farm’s mall dairy unit exported milk to the local community and their dung was the mainstay in terms of maintaining fertility. A new flock of sheep comprising 60 ewes were put to the two new rams. Meanwhile £25 had to be spent on controlling an infestation of 440 wild rabbits.

The farm grew mangles (a form of turnip), cabbage, winter bean, oats, winter wheat and potatoes. Hay was made from the grassland and cider was produced from the orchard. In the spring, large numbers of lapwing settled on the fallow and grassland in such great numbers that their eggs were collected and sold. August 6th 1914 : “War Office men came and commandeered two of my horses, both 4 year olds... this makes it very awkward as we now have no horses to change over...much of our corn is down and over ripe.”

Even with the arrival of tractors soon afterwards, farming remained back-breaking work. Against this backdrop, international political and trade relations were being redrawn, populations were burgeoning and many countries were seeking to increase self-sufficiency of food production to avoid the supply problems experienced during the war.

As more food was needed so was every bit of available land; grasslands and meadows sustained ongoing heavy losses as they were ploughed up in order to tap into their fertility. If farmers refused to comply, their farms were taken over. County War Agricultural Committees set up depots of tractors and modern farm machinery that could be borrowed by farmers and a deal struck with America when they came into the war, Lend-Lease, meant that new tractors and combine harvesters arrived on our shores.

During World War Two and its aftermath fertility declined and this was accelerated by the ‘Green Revolution’, which marked a turning point in the intensiveness of food production and a period of onslaught on wildlife, soil and water began. This revolution began in 1944 when plant breeder Norman Borlaug developed varieties of wheat that could withstand higher levels of nitrogen being applied; countries like Mexico went from hunger to self-sufficiency within 15 years. But the revolution was accompanied by displacement of people and wildlife, an increasingly intensive approach to crop production and the draining of soils natural fertility, leading in turn to an ever-increasing reliance on artificial fertilisers and pesticides. For farmers, this has been a vicious downward spiral increasingly accompanied by climate change.

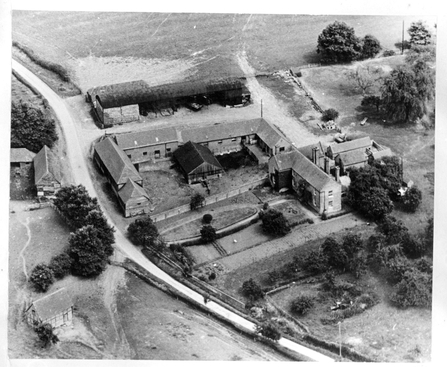

As an agronomist looking after a portfolio of over 15,000 acres, it was impossible for me not to notice the sharp declines in lapwings, skylarks, yellowhammers and earthworms as farming systems increasingly became more and more intensive. During the 1990s, there were exceptional grain prices accompanied by high subsidies – farming was making lots of money and the concept of anything other than record breaking yields year-in year-out was just not considered. But many farms were living on borrowed time – the leftover fertility from ploughing meadows was reducing, bumper yields were further depleting the soils resources, pesticide over-use was manifesting itself in resistance and soils were becoming almost entirely reliant on artificial fertilisers. Lower Smite Farm was no exception and when the farm was sold in 1979, Hereford and Worcester County Council bought it at auction with the intention of using the site as a landfill site.

Thankfully the plans never went ahead – in 1990 we leased the farmhouse, outbuildings and seven acres before purchasing the freehold in 2001. In 2002, a legacy left by a Mrs Heynes to the Trust made it possible for us to buy the rest of the farm. The Trust employed me as their Farming and Agriculture officer in 2006 to develop the farm for demonstration, community engagement and education. We consulted widely and drew up a management plan that focused on restoring soil health and meeting the key needs of farmland wildlife...adequate food, nesting habitat, winter habitat and low stress (the Big 4). Half the farm entered organic conversion in 2010 (organic isn’t the only way but we do not use insecticides or slug pellets anywhere) and the entire farm entered a ten year Natural England Higher Level Stewardship (HLS). Our farming volunteer team got off the ground in 2008, meeting every Tuesday, and has achieved huge tasks including planting over 3km of hedges, two new woodlands and 5000 trees. We have sown floristic field margins and a new meadow as well as creating a new wetland that not only provides great habitat but also filters nitrate and phosphate from the water. The area of cereals dropped by 80% as we embarked on a soil health restoration project aimed at doubling our soil organic matters from 2.5% to 5%. Over time we have formed good relationships with farming neighbours who carry out various operations such as cultivating and haymaking.

Recently one neighbour wryly said ‘This place is beginning to look like a real farm again’ – he meant that we are now producing good quality floristic hay and that whilst the farm looks tidier (fewer weeds) it is also much more diverse and is maturing nicely. The same neighbour helps our grassland restoration by bringing in hay from a wildlife site that is then spread on our HLS grassland creation field. We don’t have our own livestock but, in the event of not being able to source an organic neighbour with a shortage of grass, we do have permission from the Soil Association to bring in non-organic animals for 120 days.

Farm volunteers © Wendy Carter

Granary at Lower Smite Farm © Paul Lane

At the time of writing (September) there is plenty of grass in Worcestershire and, with no sheep heading our way yet, this highlights a core problem and challenge for the future. If we are to healthier soil with temporary leys and if we are to grow fewer cereals because the profit simply doesn’t stack up, what are we going to do with the grass? A key area is to evaluate how we manage cropping for the next three years; what is the point in growing wheat if the cost of production (£150/t) is greater than the sale value per tonne (£104/t)? Many arable farms throughout the country are in a similar boat. Moving to livestock production en masse is not the answer. I think we need to find a way to turn the grass/fodder mixes into compost to return the fertility to the soil and also into energy but it will be hard to compete with crops such as maize for biomass, which is so popular with high rentals being paid but weaknesses in husbandry are often reflected in soil erosion, run-off and water pollution. As we approach the end of 2016 there are no silver bullets. It’s been a bad year for butterflies and many insects, much put down to the cold spring, but many farms have fared badly too – weed resistance problems are getting worse and market prices continue to be poor. Despite some wildlife success (such as otter, bittern and large blue butterfly), The State of Nature Report 2016, released in September, provided bleak reading. Sir David Attenborough, who wrote the foreword, said

“The natural world is in serious trouble and it needs our help as never before.”

Meanwhile at Lower Smite, we are investing in a farming system in better shape to face the future but we need farming systems throughout the country to future proof, deliver what wildlife needs too and be paid for delivering environmental good. Perhaps the concept of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) – the benefits that our environment naturally does for us – will become the future; farmers getting paid for their land’s ability to hold flood water, filter nutrients out of farmland and protect watercourses as well as meeting the needs of wildlife and people.