25 years ago this week, a bold new framework was adopted by EU member states. The Water Framework Directive (WFD) set out overarching principles and minimum standards, to provide a common regulatory framework on water across Europe. Fast forward to today and it was expected that most waterbodies would by now be at, or very near to, their target status. So, is that the case?

First, let’s delve into what the WFD, and the target status, is…

The Water Framework Directive sets a high level of ambition

The high level of ambition set by the WFD is evident from the very first point in its preamble: “Water is not a commercial product like any other but, rather, a heritage which must be protected, defended and treated as such.”

The Directive aims to drive the sustainable management of rivers, lakes, the underground aquifers that feed them, and estuaries and coastal waters because of their clear economic, social and environmental value.

What does the Directive require? And what is the target status?

The Directive sets out core standards and key principles, including:

- Precautionary and preventive action should be taken

- Environmental damage should be rectified at source

- The polluter should pay

- Decision-making should be as local as possible

The Directive requires action to bring waters to ‘Good’ status – a measure of health which is based on:

- Ecological Status (water quality and quantity parameters)

- Chemical Status (levels of pollutants of particular concern)

Restoring waters to this state is the Directive’s default ambition because waters in good health are more able to deliver the economic, social and environmental goods that we all benefit from.

Despite being the default standard, not every single waterbody is expected to be brought up to good status.1 The Directive is not completely fanciful in its ambitions - recognising that human-caused or other pressures have degraded some sites so much that it is simply infeasible to bring them back to good health.

Whilst that may sound defeatist, it gives rise to one of the core tenets of the Directive – that where an objective is set for a waterbody, it is the highest objective that can be set whilst remaining feasible, affordable, and indeed cost-beneficial.

To drive progress, member states were required to publish River Basin Management Plans describing the actions needed to restore waterbodies to their target levels. The first round of six-year plans ran from 2009-2015, by which date many waters should have been brought to their target status. For others, countries were allowed longer to meet targets on cost or feasibility grounds, with further rounds of plans running to 2021 and 2027.

Let’s look at how England’s waters are doing.

Only 16% of England’s waters are at Good Ecological Status

In England, an objective of Good was set for 78% of our rivers, lakes, estuaries and coasts2. Yet only 16% are at Good Ecological Status, and none are at Good Chemical (or therefore Good Overall) status.

In fact, England’s waters are not predicted to reach this standard until 2063, when persistent chemical pollutants should have degraded sufficiently for our waters to again be considered unpolluted.

In the meantime, the focus is on improving ecological status.3 In 2019, England remained far off-target, and with only a partial data update in 2022 it is hard to determine whether things have improved or declined since.

The situation across the rest of the UK is similar, with all nations expected to miss 2027 targets by reasonable margins.

- Northern Irish data (2021) puts 32% of rivers at good ecological status, with both England and Northern Ireland reporting no waters meeting good chemical status due to the way in which chemicals are monitored.

- For Wales, (2024) 40% of surface waters are at good overall status.

- In Scotland, (2023) 65% of surface waters are at good or better overall status.

These figures exemplify the challenges of meeting good status in a small, densely populated and heavily agricultural country, with England’s stats the worst of the UK nations.

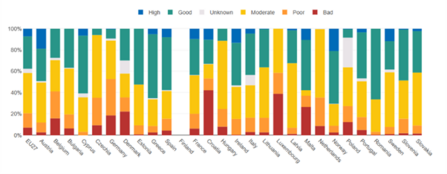

The UK isn’t alone in its struggles

Whilst the UK will fail to hit targets, it is hardly alone in struggling with this challenge. Several EU nations have similar results, with Luxembourg and the Netherlands reporting all waterbodies as being moderate at best, and even the best performers do not exceed England’s target level of 78%. Others have large chunks of data missing, meaning that the state of their waters is at least partly unknown.

There are actions that could be taken to meet the Directive requirements

In the UK, post-Brexit scrutiny sits both with bodies like the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP) and the public.

The OEP reported5 last year on the shortcomings in England’s approach to WFD delivery. It identified:

- Plans that were unspecific, not time-bound and unfunded

- Issues with how progress is communicated

- Concerns around monitoring, including of newly-emerging pollutants

UK Government’s Independent Water Commission followed, looking at regulation of the water sector and of water more generally. It too identified that we are far from meeting targets, and that strengthened WFD regulations could play an important role in meeting wider biodiversity targets, but it also raised challenges with the classification framework and the design of targets and objectives.

With Government’s plans in this area currently awaited6, the future is unclear, but there are actions that could be taken to help us meet or even exceed WFD requirements.

1. Greater decision-making at regional and river catchment levels

In line with the Directive’s support for localism, greater decision-making at regional and river catchment levels could see faster progress through local collaboration and innovation. These are all recommendations from Sir Jon Cunliffe’s Independent Water Commission.

Government has already indicated its support for an element of regional planning and could back this in the upcoming ‘Water Reform Bill’ by ensuring that England’s 100+ Catchment Partnerships are adequately supported.

Regional boards should have the ability to draw on or direct relevant budgets including farm support, water company and flood defence funding – on the latter, £300m recently announced for natural flood management is extremely welcome.7

2. Clearer reporting on underlying elements

Reporting on Ecological, Chemical or Overall status alone can mask improvements in the underlying components that make up these headline assessments. Rather than water down assessments, reporting more clearly on underlying elements will aid stakeholder understanding and inform project planning.

3. A delivery pathway showing how targets should be met

Key targets to drive forward Water Framework Directive delivery exist under the Environment Act, focused on reducing water use and pollution from farming, wastewater and abandoned mines. A delivery pathway showing how these targets should be met will help to drive local action.

4. The Polluter Pays Principle should be used to address emerging threats, such as microplastics

Existing legislation does not adequately address emerging threats such as from microplastics, pharmaceuticals and ‘forever chemicals’ like PFAS. The Polluter Pays Principle should be used to ensure that these pollutants are adequately removed from wastewater discharged to the environment, and from the drinking water that we consume.

5. All actions must be underpinned by well-resourced monitoring

Finally, all of this must be underpinned by well-resourced monitoring so that decision-making is science-based and robust. We need a clearer understanding of the sources and pathways of pollution, and the effectiveness of the solutions we employ, if we are to make faster progress towards targets.

The alternative – of pushing back deadlines and weakening targets – causes unquantified risks to our water systems, the wildlife they support and even potentially to human health.

These are not changes that many would argue for, so if we find ourselves looking back in another quarter century at our progress since today, I for one will be hoping that we stuck to the Directive’s core aim to treat water as ‘a heritage to be protected’, and that we are celebrating a happier Water Framework Directive birthday.