A year-long social consultation has found that 72% of people in the project area of Northumberland, bordering areas of Cumbria and southern Scotland, support potential lynx reintroduction. Lynx used to live in Britain until the medieval period when they died out due to hunting and habitat loss.

Missing Lynx exhibition © Trai Anfield

The consultation was run by The Missing Lynx Project, led by The Lifescape Project in partnership with Northumberland Wildlife Trust and The Wildlife Trusts. The consultation report provides the initial findings of local people’s attitudes towards lynx reintroduction and their level of support.

Now the project is working with people in the region to discuss how a potential reintroduction could be managed if it were to progress further. The partners are also urging people across the UK to find out more and have their say through a national questionnaire.

Over a thousand people in the project area filled in a detailed questionnaire in the project area. The regional consultation – which is ongoing – included:

- Almost 10,000 visitors attended the touring Missing Lynx exhibition over 103 days

- >100 stakeholder meetings and one-to-one interviews with community, farmers, landowners, foresters and businesses; 12 workshops were also held

- 1700 people completed individual questionnaires (of these, 1073 respondents lived in the project region)

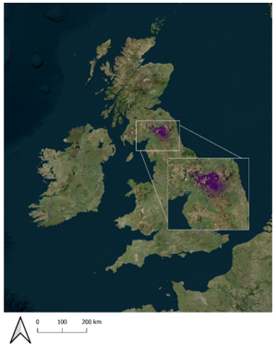

The results coincide with the publication of a new peer-reviewed paper produced by the project, ‘Exploring the ecological feasibility of restoring Eurasian lynx to Great Britain using spatially explicit individual-based modelling’. This research shows that a release of 20 lynx over several years into the Kielder forest area would, over time, create a healthy population of about 50 animals covering north-west Northumberland, the edge of Cumbria and the bordering areas of southern Scotland. It also reveals this is the only area of England and Wales with enough extensive woodland for lynx to thrive.

Lynx family © Berndt Fischer

Dr Deborah Brady, project manager and lead ecologist, The Lifescape Project, says:

“We’d like to thank the thousands of people who visited the exhibition, filled in the questionnaire or spoke to us over the last year. Now we know that the majority of local people support lynx reintroduction and we also have the scientific evidence showing that a release of lynx in north-west Northumberland could work.

“We will continue to work with local communities to consider how a reintroduction project could be managed to maximise benefits and reduce risks. We hope to apply for a licence but only once we have a plan that’s collaboratively designed with local people which sets out measures that are acceptable, feasible and can be implemented.”

Mike Pratt, chief executive of Northumberland Wildlife Trust, says:

“The fact that 72% of respondents in the project region support a potential lynx reintroduction is hugely positive. Locals are proud our region is a stronghold for threatened species such as red squirrels and water vole – so it’s no surprise that they’re in favour of bringing more back. The chances of ever seeing this beautiful creature are very rare, but communities have let us know that they recognise the benefits of restoring this beautiful animal.”

Dr Rob Stoneman, director of landscape recovery, The Wildlife Trusts, says:

“Bringing back lynx could benefit wildlife more widely – something that is sorely needed in this nature-depleted country. We have pushed many native species to extinction, and it makes sense to bring missing wildlife back where feasible. Bison and beavers have invigorated degraded habitats and this consultation shows there’s now an opportunity for us to bring back lynx too.”

Lynx © Berndt Fischer

In addition to extensive interviews and workshops with key stakeholders, the project took a group of local farmers to Europe to visit two lynx projects and livestock farmers already living alongside lynx. One of those on the trip, Lauren Harrison, a sheep farmer from Hadrian’s Wall says:

“I saw in Europe that it’s possible to live alongside lynx. The risks to livestock can be minimal and there are so many positives. Tourism is an obvious one, but I also think a more balanced ecosystem is beneficial to farmers.

“I’ve been really impressed with the approach and the professionalism of the Missing Lynx Project - I think it’s really setting the standard for reintroduction projects. Consultation has been at the heart of everything they do: they have really listened and are still keen to work with farmers to make sure any reintroduction is well managed. I’d urge other farmers to engage with them and take some ownership of the project. The wider public clearly supports a lynx reintroduction and this is a great chance to help make it happen with so little risk to our businesses.”

Adam Eagle, chief executive of The Lifescape Project

“We are so excited to hear the views of people across the UK through our national survey, which is now open for responses from people everywhere. But we also know that some people will have concerns, so it is important that everyone has the chance to express a view. The possible return of this beautiful cat is such an important topic for nature restoration in the UK, with the potential to capture imaginations and become a catalyst for engaging people in nature.”

Editor's notes

- Further information: www.missinglynxproject.org.uk

- Research article published in the Journal of Environmental Management: Exploring the ecological feasibility of restoring Eurasian lynx to Great Britain using spatially explicit individual-based modelling and available on the Missing Lynx Project website here: Exploring the ecological feasibility of restoring Eurasian lynx to Great Britain using spatially explicit individual-based modelling

- Missing Lynx Project ambassadors: missinglynxproject.org.uk/about-project/ambassadors.

- Missing Lynx exhibition: watch this short film to get a flavour of the touring show.

- Parallel project in Scottish Highlands: Lynx to Scotland

- Previous MLP release: Farming and lynx can co-exist says Missing Lynx Project

Below: map of project area and predicted growth of a lynx population 5 years after release (purple shading), used to plan the location and extent of the Missing Lynx Project’s social engagement and consultation.

Lynx – background

The lynx is an elusive and solitary cat that lives in forests across mainland Europe and there is evidence of them living in Britain until medieval times. They are roughly the height of a Labrador dog but weigh less, have tufted ears, a spotted brown and white coat and golden eyes. They are not dangerous to humans and keep their distance from people – it’s hard to see them because they like the cover that woodland provides. They prey on mainly roe deer, but also smaller mammals such as rabbits and even foxes. Lynx are mainly active at dawn and dusk – they tend to sleep during the day.

Lynx – in our forests

For the many thousands of years that we did have lynx in Britain they were a critical part of our ecosystems. But now all of our top carnivores are missing. Eurasian lynx eat mostly deer but can also eat medium-sized carnivores such as foxes and small animals such as rabbits. Their presence in our ecosystems regulated other animals and had trickle down benefits such as forest regeneration or providing carcasses for a wide range of animals, birds and insects.

Lynx – conservation efforts abroad

There are four species of lynx in the world; two are found in north America and two across Eurasia. The Eurasian lynx is one of two lynx species in Europe and has made a successful comeback since the 1970s thanks to conservation efforts, community support, habitat protection and reintroductions in countries such as Germany, Switzerland, France, Italy and Slovenia. This followed decades of hunting and habitat loss, which caused their numbers to plummet to their lowest ever in the mid-20th century. The slightly smaller Iberian lynx is found in Portugal and Spain, where breeding programmes have also seen numbers return, saving this species from extinction.

Lynx viability in northern England and southern Scotland

We now know that lynx could grow into a healthy population from a release in Northumberland. Working with experts across Europe, The Lifescape Project used data from European lynx populations in computer models to test the viability of growth and survival of a population. The forests of northern England and southern Scotland form a habitat patch where a healthy lynx population could develop. This habitat patch was the only currently suitable area of England & Wales for lynx.

The UK nature crisis

The UK’s wildlife is continuing to decline according to the landmark study, State of Nature 2023 - report on the UK’s current biodiversity. Already classified as one of the world’s most nature-depleted countries, nearly one in six of the more than ten thousand species assessed (16%) are at risk of being lost from Great Britain. The list of extinct British wildlife is long and includes the great auk, large copper butterfly, lynx and tree frog. Many species are now increasingly vulnerable, such as hedgehog and curlew, or are in danger of disappearing. Most of the important habitats for the UK’s nature are in poor condition, but restoration projects have clear benefits for nature and people, as well as for climate change mitigation and adaptation. We need healthy ecosystems for our clean water, fresh air and food security. Bringing lost species back and rebuilding our ecosystems is a vital part of tackling this nature crisis, and bringing back lynx could be part of this solution.

The Lifescape Project

The Lifescape Project works toward a world rich in wild landscapes, providing a sustainable future for life on earth. As a registered charity, our multidisciplinary team works on projects globally which catalyse the creation, restoration and protection of wild landscapes. Those projects bring together team members with backgrounds in science, technology, law, economics, and culture, to have the greatest possible chance of succeeding for the benefit of both people and nature. www.lifescapeproject.org

Northumberland Wildlife Trust

Northumberland Wildlife Trust is the largest environmental charity in the region working to safeguard native wildlife. One of 46 Wildlife Trusts across the UK, Northumberland Wildlife Trust has campaigned for nature conservation for over 53 years. It aims to inform, educate and involve people of all ages and backgrounds in protecting their environment in favour of wildlife and conservation. Supported by over 12,000 individual and 40 corporate members in the region, Northumberland Wildlife Trust manages and protects critical species and habitats at over 60 nature reserves throughout Newcastle, North Tyneside and Northumberland. www.nwt.org.uk

The Wildlife Trusts

The Wildlife Trusts are making the world wilder and helping to ensure that nature is part of everyone’s lives. We are a grassroots movement of 46 charities with more than 910,000 members and 35,000 volunteers. No matter where you are in Britain, there is a Wildlife Trust inspiring people and saving, protecting and standing up for the natural world. With the support of our members, we care for and restore over 2,000 special places for nature on land and run marine conservation projects and collect vital data on the state of our seas. Every Wildlife Trust works within its local community to inspire people to create a wilder future – from advising thousands of landowners on how to manage their land to benefit wildlife, to connecting hundreds of thousands of school children with nature every year. www.wildlifetrusts.org