My book, The Cuckoo’s Lea, is about the special relationship between birds, place and us. I travel the country to understand how birds evoke personal, emotional attachments for us to particular places. The marsh birds are a good example: think of how a curlew’s song, so mournful and desolate-sounding, adds to that solemn feel of wide open spaces.

A history of birds and place

Barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) adult singing from perch on a fallen tree at an arable farm in Hertfordshire. May 2011. - Chris Gomersall/2020VISION

Landscapes steeped in wild history

Birds have been connecting us to landscapes for a very long time. How do we know? Our place-names. We barely think about them, but they’re all around us and nearly all very old (from the Anglo-Saxon age), and nature is mentioned a lot, including hundreds of birds. This is the other central theme in The Cuckoo’s Lea: it’s a journey into the forgotten history of what people knew about the natural world around them where they lived.

A key message of my book is that by discovering the knowledgeable connections our ancestors had with their environments (even tiny birds like wrens and dunnocks appear in place-names), we can learn to be more aware of the importance of paying attention to and caring about the wildlife and habitats right on our doorsteps. For our happiness and health, we still need to be a part of our local places and communities through those ecological ties (knowing about and appreciating our links to nature) as much as anyone living 1,000 years ago.

Curlew, Numenius arquata, in flight at dusk. Peak District National Park, UK - Ben Hall/2020VISION

Plotting your wild places

In this third week of 30 Days Wild, I encourage you to get involved with nature by going medieval with names for places. Looking closely at what is in your street or vicinity can be a very satisfying way to feel connected, and you’re following in a very long tradition of paying careful attention in this way.

Get children learning more about their neighbourhoods by making maps, renaming streets or features according to what they see and hear: robin’s streetlight, swan’s pond, buzzing buddleia, nettle bridge, woodlouse corner, owl-hooting yew tree, windy oak? Can someone else make their way around using your map, identifying your new, wild landmarks? There really were maps like this in medieval times: they appeared in documents called charters and they directed readers around the boundaries of land, mentioning signposts such as the ‘otter stream’, ‘black willow’, ‘hoary thorn’, ‘thrushes’ wood’ and even a ‘dung heap’!

It’s all about close observation (and listening and feeling) of what is around you. That’s key to anyone who’d like to begin nature writing.

Start with old-fashioned note-taking: make lists of what you notice, paying attention to the tiny as well as the large and obvious, and use all your senses.

From there, try creating illustrated mindmaps of locations you visit—colourful, visual, all-senses records of your experiences of places. What these activities will do is get you really focusing on the little things that matter in our relationships with place, and you’ll find yourself more connected as a result.

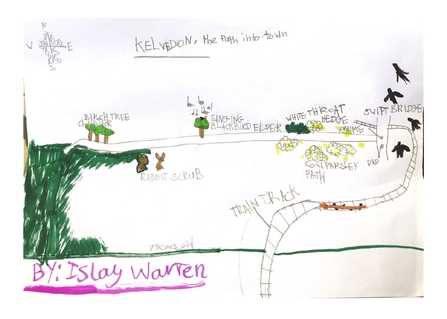

Nature map by Islay Warren - Michael's daughter

(Above - Nature map of Kelvedon, Essex by Islay Warren, Michael's daughter)

Then, you could write a short prose piece or poem with the name of a place you know as the title. But… show us a new side to that place: transform it into something that others haven’t seen by focusing on something from your list or mindmap and describing that thing (or things) in detail.

A poem about your street focused entirely on the starling you observed on a telephone wire? Or the single poppy growing on the edge of the pavement? Now that’s a real sense of place. And a very old one.

It’s a lovely thing to develop your own relationships with nature by learning about those of people living centuries ago.

Here are some further suggestions:

- Research what places in your area have nature-names and create a map. You can use Wikipedia or sites such as The Key to English Place Names and the Birds & Place Project.

- If you have a favourite animal or plant, see how many examples of place-names across the country you can find that mention this animal or plant. Tip: some easy ones are otter, crane, oak and fox.

- What can you discover about the old folklore of particular animals and plants (what people used to think and believe), such as the idea that owls foretold death and nightjars sucked milk from goats in darkness?

- Why was a daisy called a daisy or a mouse a mouse? Find out about the original meanings behind the names of Britain’s plants and animals and you’re entering the imaginations of your ancestors.

In The Cuckoo's Lea, Michael J. Warren sets out on the trail of these ghosts. Captivated and guided by the secrets of place names, he finds their stories entangled with his own explorations of places through birds all across England. The past is hauntingly and movingly present on timeless marshes where curlews cry, where goshawks are breeding again for the first time in centuries, through silent cuckoo-woods lost under concrete sprawl, in the winter roosts of corvids and an owl village that vanished centuries ago. Weaving together early literature, history and ornithology, this book takes readers on a journey far into the past to contemplate the nature of place and to discover a fascinating heritage that matters deeply to us now when so many places and their birds are threatened or already gone.

Michael J. Warren is an author, medievalist and naturalist. He teaches English in Chelmsford, was honorary research fellow at Birkbeck College, chair of the steering group for New Networks for Nature, and is currently a trustee for Curlew Action. Michael curates The Birds and Place Project, a website devoted to collecting and recording the birds of English place names.