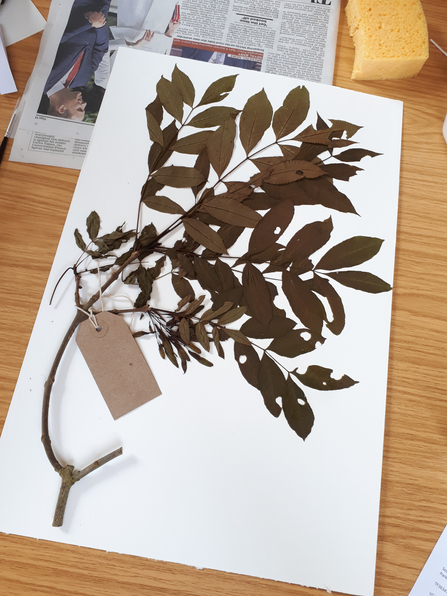

I tentatively lifted the pages of newspaper uncertain at what would be inside. My heart sank. An ash tree. Not an entire tree but enough to make gluing it onto a sheet of paper measuring 29cm by 43cm a bit tricky.

The stem was strong and robust; it had resisted the force of the plant press. From it sprouted swathes of leaves; dark olive-brown in colour. They seemed fragile like brittle silk. There was a bunch of keys, still small and under-developed.

The whole thing looked ancient. It could have been like this for centuries but I know this specimen was collected in May this year; four months ago. It was snipped from the rest of the tree on a training day for the Lincolnshire Wildlife Trusts’ #LoveLincsPlants project. Fifteen of us were being trained by botanists from the Natural History Museum on how to collect and press plants.

Specimens were laid between sheets of newspaper ensuring all the characteristic features could be seen. Then they were squashed between layers of card and felt, and placed in a wooden frame. The frames were put in a drying unit – converted from a honey warming unit from a local beekeeping supplier.

Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust

The Natural History Museum botanists returned in September to show us how to mount the specimens. They have high standards. We are told this is about science not creating something that's aesthetically pleasing. Although I am allowed to remove some of the leaves from my ash as long as the cut stem is clearly visible. Researchers must be able to see that material was removed.

The concentration in the room is palpable. It’s a relaxed concentration though, the kind when you’re entirely absorbed at the task at hand. This tactile process of preserving plant specimens has been used by botanists for centuries. The pressed plants can survive for hundreds of years, especially when stored in temperature-controlled, pest-free environments.

Through the #LoveLincsPlants project, a herbarium of 8,000 historic specimens collected in Lincolnshire has been passed to the Natural History Museum. At the museum it can be catalogued, digitised, safely stored and made available for research.

Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust

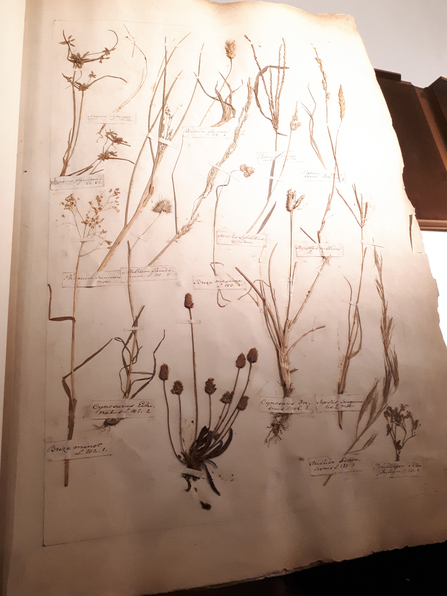

A few months later I get the opportunity to visit the museum and see a handful of the 800,000 specimens in the British and Irish Herbarium. We also visit the historic herbarium. On the specially made shelves are some of the biggest books I have ever seen. Leather bound volumes with plant specimens from around the world including from Captain Cook’s first voyage from 1768 to 1771.

Cook's first port of call on the voyage was Madeira; as soon as the book is opened my eye is drawn to something familiar: a specimen of quaking grass, my favourite grass, probably collected by Joseph Banks.

Banks, of Revesby Estate in Lincolnshire, was the inspiration behind the #LoveLincsPlants project. He would later be knighted and hold the position of President of The Royal Society for 41 years. But in 1768 he was young, ambitious and wealthy. He was appointed to Cook’s expedition as the official botanist and paid for seven others to join him including naturalists, artists and servants from his estate.

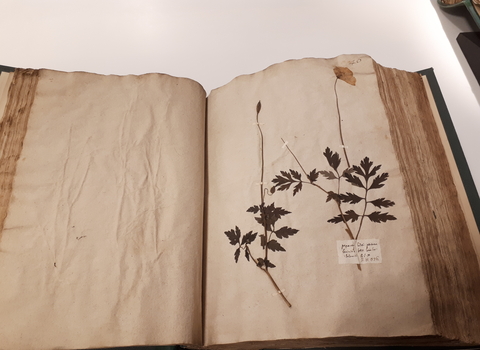

During the voyage, Banks and his cohort collected specimens of over 3,600 plant species; around 1,400 were then new to science. The specimens of Madeira holly remind me of my ash specimen, the leaves have a similar deep olive-brown colour even though they are 250 years older.

We step back in time further to a collection of British plants made in the 1690s by Lincolnshire-born Rev Adam Buddle. His collecting was methodical and in 1708 he completed a New English Flora. It was never published but was later examined by Carl Linnaeus. Perhaps impressed by Buddle’s work, Linnaeus named an entire plant genus after him; the buddleia.

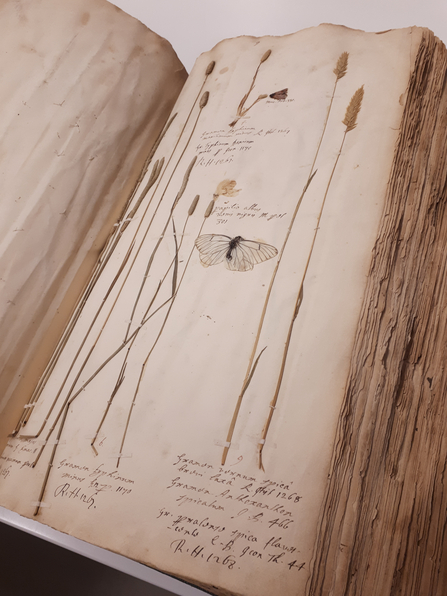

Buddle never knew of the existence of buddleia, it was discovered in western China 150 years after his death, but it seems appropriate. Buddle liked to add a little extra bling to his herbaria. Amongst the flowers are pressed bees, beetles and butterflies.

Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust

We huddle around the books, in awe at their contents and their age. I imagine the well-to-do gentlemen who collected and preserved the specimens. They are gathered in a drawing room after dinner, showing off their latest finds. A butterfly caught in the prime of its life and pinned to a piece of card. A plant plucked from the ground and pasted into a book, its life squeezed out of it.

I don't think I have much in common with these men, if I’d been alive at the same time I wouldn't have been allowed in the same room as them. But I share a fascination with the natural world and I collected and pressed wild flowers as a child. I still have them now, trapped, Blue Peter-style, behind sticky-backed plastic.

As I dab glue onto the leaves of my ash specimen, I think about my childhood herbarium. It helped me learn about wild flowers and encouraged my interest in natural history but is of no scientific value. My ash specimen may be different. As part of the new #LoveLincsPlants herbarium it could survive for centuries. It may give an insight into how ash was affected by ash die-back disease or changes in distribution to ash trees.

Both Banks and Buddle collected plant specimens from sites where they are no longer found. Where will ash be found in 50 or 100 years time? Perhaps future generations will look at it in awe like we looked at the herbarium of Banks and Buddle.

Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust

Written by Rachel Shaw, Senior Communications Officer, Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust

#LoveLincsPlants

Thanks to funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust is leading a project to preserve Lincolnshire’s botanical heritage and inspire and train future botanists.

Inspired by Sir Joseph Banks, an 18th Century Lincolnshire naturalist who voyaged around the world with Captain Cook, the project aims to:

- Introduce children to the importance of plants in the modern world,

- Inspire young people to train as the botanists of the future,

- Train volunteers in traditional plant collecting and archiving skills,

- Preserve Lincolnshire's botanical heritage with a new collection of Lincolnshire plants.

As well as the Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust, other project partners include the Natural History Museum, Lincolnshire Naturalists' Union, Sir Joseph Banks Society and the University of Lincoln.