This year, we are commemorating many important anniversaries. 20 years have passed since the Falklands War, 60 years since Queen Elizabeth came to the throne, and a full century since two terrible events: the sinking of the Titanic, and the tragic death of Captain Scott and his men on their return from the South Pole.

A century has also gone by since an even more momentous event for the history of wildlife conservation. For it was in 1912 that a wealthy banker and amateur entomologist, Charles Rothschild, set up the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves, now regarded as the launch of the Wildlife Trust movement in Britain.

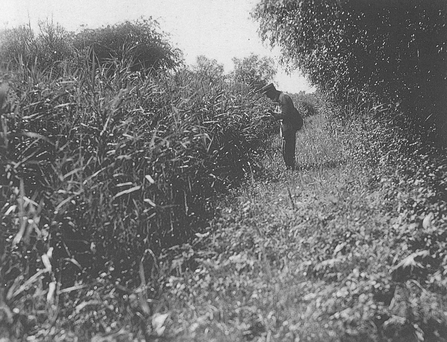

Rothschild was no mere dilettante, with a passing interest in nature. He was a leading entomologist, specialising in fleas, and in 1899 he had established the UK’s first nature reserve, at Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire.

But it was his visionary realisation that 20th century Britain would need permanent havens for wildlife that marks him out as the true father of nature conservation.

The outbreak of the First World War, in 1914, was a huge setback for Rothschild’s embryonic movement. But despite war and illness – he suffered from the debilitating disease encephalitis – he persevered. And in 1915 he produced a list of almost 300 wildlife sites up and down the country, which he felt were ‘worthy of preservation’.